Sion Kim

Sion Kim (김석연) is a Korean beekeeping expert with extensive knowledge of traditional beekeeping methods and the healing properties of bee venom. Having practiced for many years, he is experienced in natural healing effects. His expertise includes caring for bees and using bee venom therapy, a practice valued in traditional medicine.

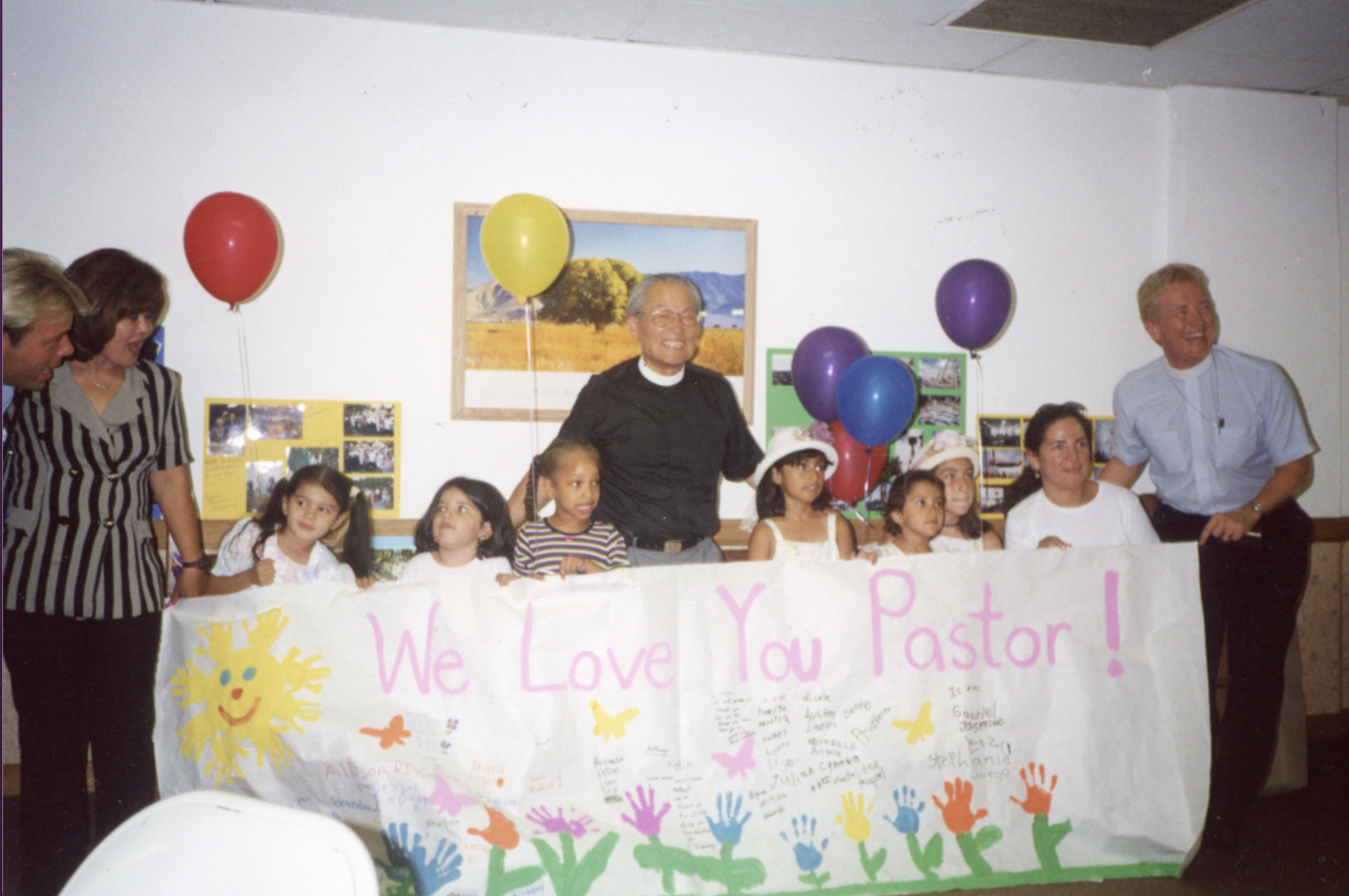

He is a retired pastor who made a living as a handyman. Now, he is busy gardening, raising chickens, and keeping bees.

Stings That Heal: The Power of Bee-Venom Therapy

Interview by Alexander Perez Callahan, Timothy Lee, and Jonah Lee

What is your name, age, and place of birth?

I am now 87 years old, and I was born in 1937 in Korea, Gyeonggi Province, Icheon. My Korean name is Kim Seokyeon, but in America, I'm Sion Kim.

How do you identify by generation, race, ethnicity, gender, or preferred pronouns?

I don't know, really. I'm the old generation. People say I'm the old generation in common parlance. I'm Korean and a white-clothed person.

So, you said your hometown is Seoul. Did you grow up in Seoul?

My hometown is Icheon, and I lived in Icheon until I graduated from middle school. Then, I came to Seoul and went to Gyeongsin High School and lived in Seoul.

What was your childhood like?

I lived in the countryside as a child, in my hometown where I was born. I was born in a rural area called Daewol-myeon, Icheon, Gyeonggi Province, and my family was farmers. I grew up helping out with the farm work.

Tell me about your family. How many family members did you have, and what were your parents’ occupations?

Since I grew up in a rural area, my father and mother were farmers, and I had two older brothers, two older sisters, and a younger brother, so I was the middle child

You live in Koreatown now?

Yes, when I first came to the US, I lived in Koreatown.

So, you immigrated to Koreatown and lived there your whole life?

Yes, I've lived in Koreatown ever since.

What year did you immigrate?

I came to the US in April 1980.

So, you’ve been living in Koreatown for almost 40 years now. What’s the memory you hold dearest about Koreatown?

During the April 29th riots, we had a really hard time. At that time, the unity of the Korean people was great. Seeing all those Koreans from all over the world coming together, shouting slogans, and dealing with the April 29th riots, I felt we were really united.

What is your favorite place in Koreatown?

Even now, I usually go to Koreatown Plaza and Galleria Market in Koreatown. When I go there, I meet my friends there. That's where all the meetings take place.

Now that we've covered the basic questions, let's move on to the next question. When and why did you move to the United States? How is living in the United States different from living in Korea?

I felt uncomfortable with the social structures while living in Korea. When I came to the US, everything felt very comfortable, and it was much better than Korea.

What were your early medical experiences in Korea?

I don't quite understand.

Do you remember the Korean War?

Yes.

How do you think the Korean War and its aftermath affected you?

I was in elementary school, and liberation came when I was young. Soon after, the Korean War broke out. I am from a generation that experienced liberation and the Korean War. Amid the Korean War, we fled during the January 4th Retreat and rebuilt our lives. We lived through the war in many ways. We lived a very difficult and hard life.

Did you have a Japanese name by any chance?

Japanese name, yes. I lived during the Japanese colonial period, so I changed my name to a Japanese one during that time, so I didn't use the "Kim" surname. I changed my name to Kaneoka, a Japanese one. My Korean name is Kim Seokyeon, but I lived under that Japanese name, Kaneoka Seken, during that period. I started elementary school during the Japanese colonial period and had to take a test to get in. The test was in Japanese, and I passed, but they put a rock down and asked me what it was, and I couldn't answer that. However, I passed and went to school. When I was in first grade, it was wartime. I was a very young child at that time, but they were very strict with me. We had military training. Going to school during the Japanese colonial period was very difficult.

Do you have any medical experience in Korea?

I haven't obtained any medical experience in Korea, nothing like that.

What traditional healing practices do you engage in?

Oh, yes. When I came to the United States and was doing ministry, there was an oriental medicine doctor among our church members. He performed apitherapy with bee stings. That's when I learned about bee venom treatment. I still perform this treatment using bee venom on several people every week.

Where do you think your motivation for healing work comes from? Is your motivation of a religious nature, or is it related to your childhood memories or experiences?

No. When I was a pastor, there was a doctor who performed bee venom treatment. My tooth was really hurting because of periodontal disease. The doctor told me to try bee venom treatment for that pain, so I did. The tooth that was hurting fully recovered the next day after receiving the treatment. My tooth was very loose, but after the treatment, the pain disappeared, and the loose tooth stuck. That's when I realized that bee venom treatment was amazing. It was quite effective and worked in mysterious ways. From then on, I became interested in bee venom treatment and have treated many people with it.

We want to know about the bee venom treatment process. So, can you tell us how the process works?

Well, the bee venom treatment process is quite easy to use because it doesn't require any great skills or specialized knowledge. It's just a traditional folk remedy that's been passed down from generation to generation. It doesn't require specialized knowledge like Western medicine, and anyone can do it easily, which is its advantage. No side effects are associated with the bee venom treatment, and it is not addictive. The more you get the treatment-- The most effective thing about bee venom treatment is that it purifies the blood, so the more you get it, the clearer your blood becomes. When your blood becomes clearer, your body gets better. That's why I think bee venom treatment is the best.

How is bee venom treatment different from other traditional healing methods? I want to know more about what makes it different and special.

Unlike general medicine, anyone can perform bee venom treatment since it requires no specialized knowledge. It has no side effects, and it's not addictive. Hence, I think it's the most convenient and effective healing method.

Is bee venom therapy a type of acupuncture?

Yes, we could say that it's almost the same as acupuncture. Acupuncture has a physical effect because the needle is inserted. Bee venom therapy has a physical impact like acupuncture, but unlike acupuncture, bee venom treatment involves injecting bee venom into your body, so there is a chemical effect as well. Also, acupuncture has a physical effect only when the needle is inserted, but when bee venom is injected, the area where the bee venom was injected becomes hot, so the healing effect is much better. Bee venom treatment is three or four times more effective than acupuncture. You can see it that way.

How did your life experiences influence your decision to start performing bee venom treatment? How do you feel your life has changed since you started practicing it?

Well, the important thing about bee venom treatment is that as people live, as they get older, they naturally start to experience pain in various places. Their hands and feet hurt. They feel pain here and there. Whenever that happens, if they get bee venom treatment, it magically gets better. As they get older, if people get treatment with bee stings whenever they get sick, it will be quite effective. Even now, when people complain about pain, I perform bee venom treatment and get a lot of positive feedback.

What lessons have you learned from practicing bee venom treatment?

Yes, bee venom contains histamine, which can cause problems for people allergic to histamine. There will be side effects if you perform bee sting treatment on someone allergic to histamine. For example, a person came to get bee venom treatment because of a toothache. After getting bee venom treatment, that person immediately gets hives and a fever, and the side effects are very severe. We take preventive measures, and it gets better, but the person comes back a few days later to get the treatment again. I tell them they can't because they're allergic, so they take allergy medicine and come back. I perform bee venom treatment on them and see the pain go away. It's a bit risky, but bee venom treatment is relatively safe if you just avoid allergic reactions.

How do you balance traditional and modern healing methods?

Yes, modern medicine now, so to speak, treats symptoms, but this traditional treatment, the bee venom treatment, is not that kind of treatment. It's a fundamental treatment. Hence, if we combine traditional medicine with modern medicine, the effects and results should be better.

Yes, as you said, people nowadays don't know much about traditional healing methods. What do you think would happen if this became more widely known and more respected?

Yes, bee venom treatment has been popular in the West since ancient times. I know that in the rest of the West, bee venom treatment is still preferred more than in the US. In the US, bee venom treatment is illegal. It cannot be legally practiced. In the US, bee venom treatment is practiced, and Americans also have bee venom treatment unions, and members of the unions get bee venom treatments, thereby avoiding the illegality and practicing bee venom treatment. I think that if the US legalizes this traditional medicine and traditional treatment method and combines it with modern medicine, and we practice both simultaneously, the overall treatment effects will improve.

When you feel like you need healing, who do you turn to?

If I want treatment, I must go to my primary care doctor.

Can you tell me more about that?

When I get sick, I have my own doctor. When I go to the doctor, he will send me to the place where I need to go. That's how I get treatment.

Okay, so this might be a little tricky, but what was the proudest moment in your life?

I am most proud of being a pastor. As a pastor, the most rewarding and valuable moments are when I am doing ministry.

Can you tell me more about being a pastor?

I originally had no intention of becoming a pastor, but one day, I suddenly wanted to go to a prayer center. After going to the prayer center, I wanted to go to the seminary. I went to seminary and became a pastor. Before becoming a pastor, I only attended church once or twice a year. When I think about it, I didn't become a pastor on my own, but God forced me to do pastoral work. That's why I became a pastor. I've never regretted becoming a pastor. Pastoral work is the most rewarding and valuable work for me. This was my train of thought when it came to becoming a pastor.

Okay. I'm curious about what prompted you to choose this field of work, whether it's related to bee venom treatment or pastoring. Was there someone who guided you, or was there an event that prompted you to go down that path?

Well, no. As I said before, I became a pastor without having the intention of becoming one, but God led me there. I can't help but think so. It wasn't my will but God's will that led me to become a pastor. That's what I think.

As for the ministry and bee venom treatment, as I said before, when I was a pastor, there was an oriental medicine doctor in our congregation, and he performed bee venom treatment. That's where I learned bee venom treatment, and with what I learned, after I retired, I considered it my mission and have been doing ministry and performing bee venom treatment until now.

Let's go back a little bit. I'd like to hear more about your past career and other experiences.

I grew up in the countryside, so I was very interested in farming and livestock. When I was young, I really wanted to do well in livestock farming. My family was farmers when I was young, in middle and high school.

At that time, we raised pigs, chickens, and rabbits, and I started doing livestock farming. Then, at some point, the Gyeonggi Provincial Office asked me if I could learn how to raise dairy cows. I thought I'd go to Japan and learn how to raise dairy cows. The Gyeonggi Provincial Office sent me to Hokkaido, Japan, and I went there for dairy farming training.

I went to Hokkaido and studied at Hokkaido Agricultural University. Also, there was a junior college abroad. I went there and studied, and I mainly visited livestock testing centers, chicken testing centers, pig testing centers, and cattle testing centers, and studied on field trips. Then, I came back to Korea, and I wanted to do that business on a large scale.

I wanted to make money, and my family had a big mountain, but my father sold that mountain, and I lost the place where I could do livestock farming. I couldn't do livestock farming, so I came to Seoul and did this and that business, and eventually, I came to the United States.

Do you remember when exactly you immigrated to the United States?

Yes, it was on April 30, 1980.

You remember the date. Do you also remember anything about that first day? The memory of April 30.

My first memory is getting off the plane and coming to LA. Some kind of grass was on the side of the road, like sweet potato vines. So, I thought, "Hey, in America, they grow sweet potatoes on the side of the road." But it wasn't a sweet potato. Now that I think about it, it was--I forgot the name. It was a tree grass. And as I was entering the country, from the airport, there was this oil gushing out from oil drilling. I can't tell you how amazing it was. It was like this thing going back and forth, and they said they were selling oil. I thought, "Wow, America is truly a blessed land."

Before coming to America, you must've made plans of what you wanted to achieve here. Looking back, did you live up to that plan, or is something different from what you planned?

When I came to the US, I was invited by a Christian newspaper here. I first went to work at that Christian newspaper, or in other words, the media business. However, when I came here, it wasn't that easy. Since I was a pastor, I had no choice but to go straight into ministry, so I started to work at a church right after I immigrated. I didn't go after it.

Someone came to the church and asked me to be their pastor, so I took over that church and pastored it. It was a Presbyterian church, a sister church, and I worked there for about 5 years. Then, I graduated from a Methodist seminary in Korea. I was a Methodist pastor but thought it wouldn't work out. So, after about 5 years, I started a Methodist church called Hanbit Church. After a while, I went to a Lutheran church in the US and worked as a pastor at a Lutheran church until I retired.

Is it safe to say that you have lived as a Korean-American for over 40 years?

Exactly.

What do you think about your experience living as a Korean American?

I don't know, really. Maybe I feel that way because I'm a first-generation immigrant, but I'm a citizen of the United States, and I just live like a Korean. Whether it's in Korea or America, I just live as a Korean.

Okay, now let's move on to the closing questions. We have three people interviewing you. Do you have any advice or lessons to share with us? Please tell us if you do.

Now that I'm older, health is the most important thing in the world. Money is important. Fame is important. Everything is important, but as I age, nothing is more important than health. I had a lot of friends, but they started passing away one by one, and almost all of them are gone now. There are only a few left.

Always take care of your health and stay healthy. When you go to church, people usually tell you to pray, but more than that, we need to live positively. What I mean is that what happens to you in life is a reflection of what you say and think. So, if you live positively, you can live a successful life. That's my point.

Okay, so, now, the last question. You can take some time to think about your answer. What kind of person do you want to be remembered as, or how do you want to be remembered?

Yes, sure. When you die, you shouldn't hear people say, "Oh, no, he died." When you die, you want to hear people say, "Oh, he was a really good person." That's my opinion.

What do you mean by "He was a good person"?

I want people to remember me as a good and kind person. That's what I mean.